A walk in the woods often involves looking up and admiring the trees over our heads. Under our feet and out of sight are organisms that help those trees thrive, allies that trade nutrients for food. These barterers are called mycorrhizal fungi.

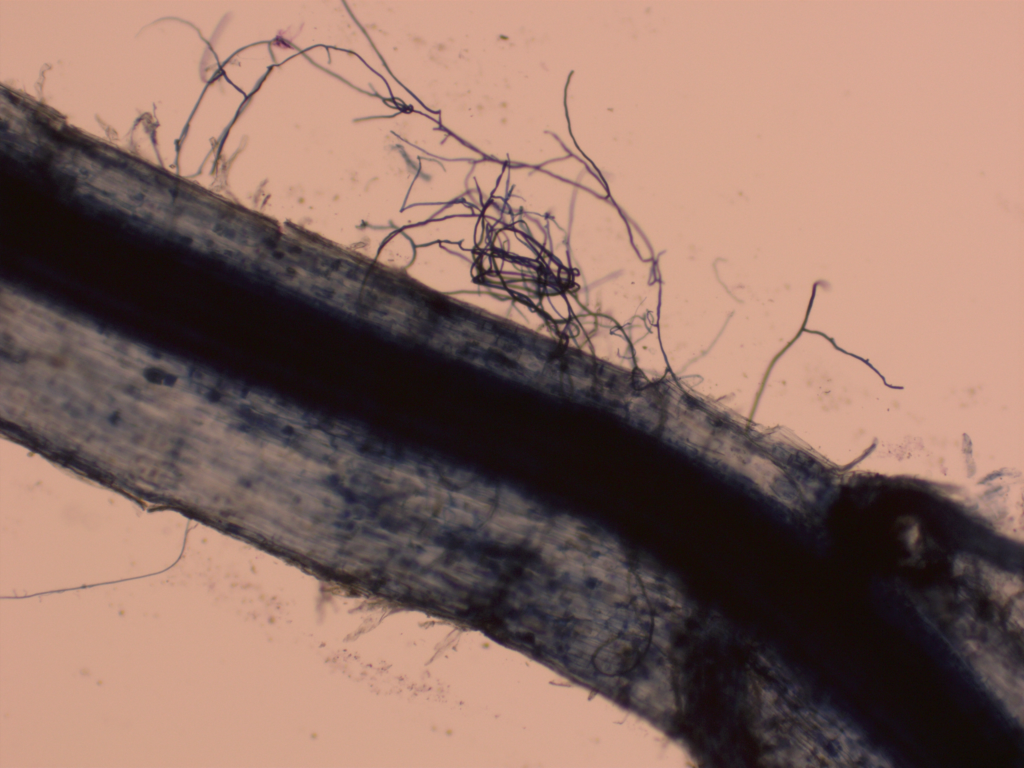

Mycorrhizal fungi form partnerships with plants using microscopic thread-like structures called hyphae. Hyphae navigate their way inside plant roots and extend out into the soil, growing faster and farther and accessing more nooks and crannies in the soil than the plant’s roots can.

Microscope image of mycorrhizal hyphae inside a flax root and spreading out from the root surface

This relationship allows plants to access nutrients and soil resources from a much larger volume of soil than the roots can alone. The fungi, which are more closely related to humans than plants, exchange the nutrients they scavenged from the soil for sugars from the plant.

This boost of nutrients allows plants to resist stress better; plants with mycorrhizal fungus associations generally have better drought tolerance and more pathogen resistance than those without. Mycorrhizal fungi can also mediate the uptake of toxic ions in the soil. They can exclude things like heavy metals while recruiting nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients plants need.

Mycorrhizal fungi offer other benefits as well. The hyphae are very effective at binding soil particles by creating net-like structures or emitting sticky compounds that glue soil particles together. These soil packets allow air and water to pass through, which improves soil quality. The hyphae holding the soil in place can also help prevent erosion.

Most plant species have mycorrhizal fungus associations, some of which are obligate, meaning one or both organisms depend on the other for survival. But not all plants form these relationships. Those that are not host plants for mycorrhizae are called non-mycorrhizal. One study showed that many common weeds, like lamb’s quarter, shepherd’s purse and knotweed, don’t need them. Weedy plants are more likely to be successful if there are fewer things to depend on.

Other plants, like cabbage, spinach and rhubarb, are also non-mycorrhizal. Caley Gasch, a research assistant professor of soil science at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, explains that growing non-mycorrhizal plants in the same plot of soil year after year will result in low mycorrhizal fungi, which could be detrimental to any crops planted that benefit from those relationships.

Caley Gasch grows plots of flax on the UAF farms in Palmer and Fairbanks to understand how it affects soil quality in Alaska.

One way farmers deal with this is by planting cover crops, which aren’t necessarily grown as crops but rather to feed and protect the soil when cash crops aren’t growing. Gasch studies how cover crops can be used in Alaska to improve soil health.

While some plants support the growth of mycorrhizal fungi better than others, these fascinating organisms are common and disperse easily. There isn’t much question about where to find them.

“You most definitely have mycorrhizal fungi in your soil,” Gasch says. “I’ve worked in reclaimed mine land, some really depleted soils, agricultural soils that have been heavily abused, and I have yet to find a soil that doesn’t have some form of mycorrhizal fungi in them.”

Flax is one of Gasch’s favorite cover crops, and she calls it a “mycorrhizal super host.” It can support many mycorrhizal fungi and boost the fungi population in the soil. Flax has light purple petals perched on spindly stems. A look inside its roots shows tissue dark with hyphae.